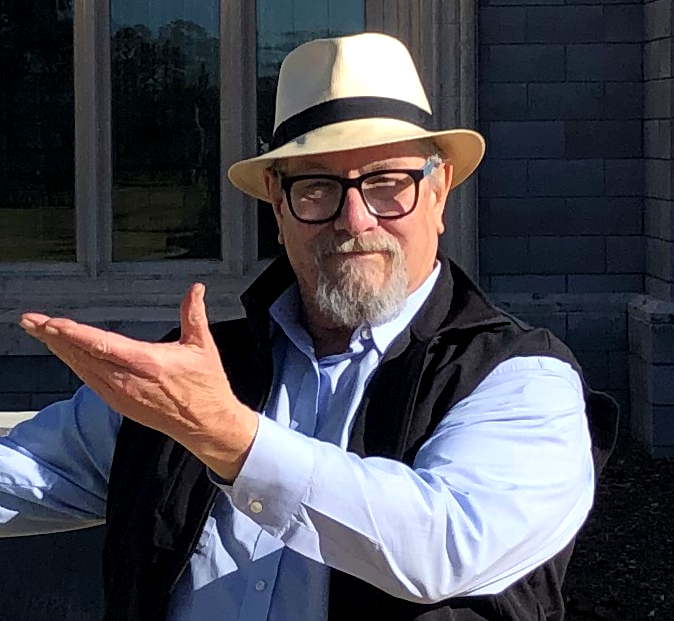

Poet. Teacher. Mentor.

My Sad Captains

by Thom GunnOne by one they appear in

the darkness: a few friends, and

a few with historical

names. How late they start to shine!

but before they fade they stand

perfectly embodied, allthe past lapping them like a

cloak of chaos. They were men

who, I thought, lived only to

renew the wasteful force they

spent with each hot convulsion.

They remind me, distant now.True, they are not at rest yet,

but now they are indeed

apart, winnowed from failures,

they withdraw to an orbit

and turn with disinterested

hard energy, like the stars.

Thom (Thomson) William Gunn, poet, born August 29 1929; died April 25 2004….

======

No. Wait. Do not go.

[ 1929-2004] A bracket of dates and life moves forward. If we were like the beasts that we keep that would be the whole of it. But we move forward carrying the past with us. It is true that age and the ever-spiraling cascade of experience force us to discard large files of memory along the way, but if we are wise we keep those memories that sustain us and let the rest pass.

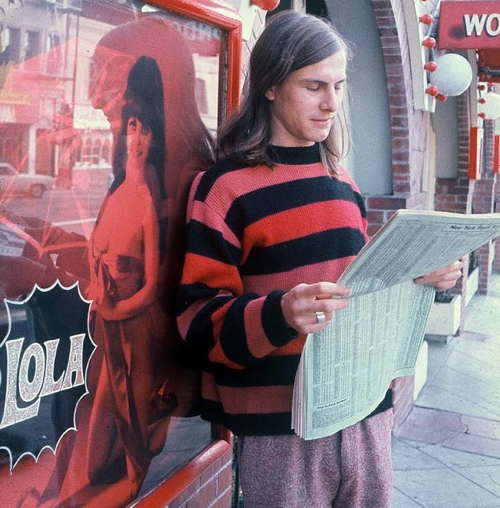

It is 1967 and I’m living with six other crazed young artists and hipsters in The Green House off Telegraph south of UC Berkeley.

The Green House was not a special place for the time. It was, in that time and in that place, ordinary. The most ordinary place in the world. If the Green House was neither real nor natural, it was fraught with a strange excitement, fecund with endless possibility. It was built of a metaphysic so loose that the most absurd accident could happen and it would only be a part of the Grand Design. It was a place where revelation and prophecy were daily events, the Second Coming scheduled for tomorrow after lunch, magic considered merely another, older branch of science, poetry an acceptable mode of speech, and caricature a widely appreciated attitude. As far as we know Rasputin, William Blake, St. Teresa, and Walt Whitman had never lived in The Green House, but they would have been welcome if they had wandered in.

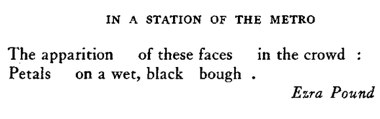

1967: Because there’s a war on, I’m trying to stay in school. But because there’s a war on I’m trying to leave school. I’m also trying to become a poet for reasons that are now obscure other than it seemed like ‘a good idea at the time.’ Off the kitchen in The Green House is a small mud room with a screened window. Nasturtium and morning glories have twined across the screen and late into the night I sit scribbling and typing one attempt at poetry after another only to abandon most of them at first light. Dawn always reveals a small pool of crumpled sheets filled with errors, false starts, bad endings, failed metaphors, forced similies — all the detritus of …

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it… — Eliot

It had not been my habit to throw anything away the previous year. Everything I wrote seemed to my young mind to be touched with light. Now I knew it had been garbage and had destroyed most of it. How did I know that? Because I had been fortunate enough to find myself in a poetry composition class taught by Thom Gunn.

1967: How many teachers do we have during our formal schooling? Two or three dozen? Fifty at most. How many do we remember? I remember three. A science teacher and a drama teacher in high school, and Gunn. I don’t remember Gunn because of how or what he taught, although that was part of it, I remember him because of who he was.

I remember the craggy, pitted face easily moved to laughter and a sensibility moved to kind despair when he was forced to experience a particularly bad line from one of his students. I remember that the class was formed of about 12 students and that on any given day at least ten were baked to a crisp. But that didn’t mean Gunn didn’t get our attention. How could he not? He was not only an elegant poet, an inheritor of the Tennysonian tradition in English poetry, but he was an elegant man.

Gunn commuted in from his other life in San Francisco on a powerful motorcycle in leather and Levis. Then, before taking up his duties as a teacher, he’d change into what had to be bespoke English Suits and cowboy boots. It was a look that the students in his class — mired as we were in the hippy-regalia of the time — could not hope to emulate. But it was a look that spoke of refinement and manliness at the same time. It was not too much to say that we worshipped the man.

Unlike other ‘established poets’ I’ve run into here or there over the years, the hours spent in Gunn’s class were never about himself or his work. We were always asking him to read to us from his work, but he never did. What we were there to discuss, he always reminded us, was our work and the work it obviously needed.

And work we did. I’ve never pushed so hard on the craft as I did during that semester. Because that was what Gunn was about, the craft. Not The craft was not about nor was the craft interested in your feelings or your petty psychosis, not the confessional spew so popular at the time. Gunn had little patience for that even though he was invariably kind about pointing it out. What Gunn was interested in teaching was the one thing he knew he could teach: the craft, the rhetorical shape, and the internal beat, the way in which you could put words together to get a specific emotion back from the reader; the painting techniques of poetry; how to draw from life with words.

Most of the time, you failed at the craft since you’d been taught that craft was a foolish tool and that emotions were all that mattered. But slowly, with his remarks in class and his reactions to the work you submitted, you came to understand that you were actually improving. In hopes of improving more, you bought his books and internalized his poems. I have all his books now, the oldest of which I bought in 1967. I’ve read through and around them many times and they never fail to enhance and expand my life.

Gunn was kind and unsparing with his criticism, but he held back his praise. Somewhere I still have a sheet of paper with his polished handwriting telling me how vivid and effective he thought it was. I kept it pinned in front of wherever I was writing for years. It strikes me now that I’d really like to find it.

In time the class ended, summer came on, and I left the University and fled to Europe. Several years passed and I was working in an office south of Market Street in San Francisco. I was walking back to the job while waiting for a light, a motorcycle pulled up next to me at the curb. Black motorcycle. Helmeted rider. Bespoke English three-piece suit. Cowboy boots.

Recognizing me he lifted his visor and smiled that smile that made the day brighter. Held out his hand and we shook. The light changed and I said, just to be clever in the way that young men are, ‘Man, you gotta go,’ a phrase that opens one of his motorcyclist poems, “On the Move.” He laughed, nodded, hit the throttle, and faded away down the long boulevard.

I never saw him again, but like all teachers and mentors that have touched our lives, he’s never really been absent. More than once over the years, I wanted to seek him out if only to thank him for what he’d added to my life. That always seemed beside the point. Now, to my regret, it is too late. Still, when I think of him or read his work as I will until my time arrives, I’ll always carry the memory of those classes and the long nights working amid the growing pile of crumpled paper on the floor in The Green House. In the end, that’s what the great teachers and poets leave us, the memories that live, the memories we choose to carry all our lives.

![Allen Ginsberg: The Interview, <strong> ➡ 1972 ⬅ </strong> [Republished by unpopular demand] ginsbergnirvana](https://americandigest.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ginsbergnirvana-150x150.jpg)

Gerard Van der Leun

Gerard Van der Leun

Your Say